K Siegersma1, E Rozeboom, PhD1, P Riva2, V Agnus, PhD3, L Goffin, PhD4, A van der Schot1, B Dallemagne, MD3, S Perretta, MD3. 1Technical Medicine, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2Institute of Image Guided Surgery, Strasbourg, France, 3IRCAD, Strasbourg, 4ICube, University of Strasbourg, France

INTRODUCTION: The increasing development of interventional endoscopy raises the challenge to teach and learn complex endoscopic procedures. Today experts are facing the challenge of explaining precisely an elaborate choreography of movements, while novices are confronted with a broad range of hand, wrist and shoulder movements each resulting in different scope. The teaching strategy of endoscopy could benefit from a dedicated motion library that deciphers the operator’s motion and the consequent endoscope response. A simplified endoscopic language made of individual motions/words could greatly shorten the learning curve. This study aims at exploring operator and endoscope motion tracking to identify and represent key movements in flexible endoscopy.

METHODS AND PROCEDURES: Six experts and three novice endoscopists performed standard EGD on a living porcine model. Participants were asked to repeat the procedure 3 times body mouvements and posture were recorded using 17 wireless motion trackers (Xsens MVN Awinda, Enschede, NL.) placed at cardinal points and axes of movements (wrists, arms, legs, torso). Endoscope motion was recorded using a magnetic tracking catheter consisting of 8 magnetic probes, placed, in the working channel of the endoscope (Aurora, NDI, Waterloo, Canada). Both the endoscopic image and an external video of the operator were recorded for motion analysis.

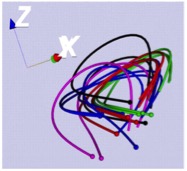

RESULTS: Motions of both operator and endoscope could be synchronized and represented in videos for all participants (Fig. 1). Experts completed the assignment in an average 78 ± 42 seconds, whereas novices in an average 235 ± 60 seconds. Although the final endoscope configuration at duodenal intubation was similar for all participants (Fig. 2), the route to reach this end-point was different between experts and novices, both in endoscope trajectory and body motions. Experts steered the endoscope along a smooth path, with on average 3 ± 2 attempts required to intubate the duodenum, while novices needed on average 6 ± 2 attempts for successful intubation, with a a chaotic trajectory. Novices required bimanual actuation to steer the endoscope wheels and kept a more still posture, while experts used the right hand on the scope shaft and liberally used upper body motions and the left arm to rotate the endoscope.

CONCLUSIONS: Motion tracking of the endoscopist and endoscope gave can provide new insights in the way we understand, teach and learn flexible endoscopy and could be as a promising educational support to shorten the learning curve.

Fig 1 Fig 2

Presented at the SAGES 2017 Annual Meeting in Houston, TX.

Abstract ID: 80086

Program Number: P276

Presentation Session: Poster (Non CME)

Presentation Type: Poster