This may be a difficult subject matter for you and your patient to talk about. Be assured, all major organized religious groups encourage and recommend the COVID-19 vaccine. Listed below are references and websites you can direct your patient towards to help them make an informed decision with regards to their religious concerns against the COVID-19 vaccine.

Pope Francis video message approving the COVID-19 Vaccine

https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/248714/pope-francis-ad-council-collaborate-to-promote-covid-19-vaccines-in-the-americas

Statement from the Vatican approving the COVID-19 Vaccine

https://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/en/bollettino/pubblico/2020/12/21/201221c.ht

Catholic US Bishops approve the use of the COVID 19 Vaccine

https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/46899/catholic-us-bishops-approve-use-of-covid-19-vaccines-with-remote-connection-to-abortion

Christian Connection for International Health Vaccine Campaign

https://www.ccih.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Faith-Leaders-COVID-Vaccine-Factsheet.pdf

Central Conference of American Rabbis Support COVID-19 Vaccinations

https://www.ccarnet.org/ccar-responsa/nyp-no-5759-10/

Orthodox Union COVID-19 Vaccination Guidance

https://rabbis.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Guidance-re-Vaccines.pdf

Dalai Lama Urges other to get vaccinated

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-56310274

National Muslim Task Force and the National Black Muslim COVID Coalition (NBMCC) on Ramadan 2021 and COVID-19 Vaccines

https://isna.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Press-Release-NMTF-Ramadan-Statement-4.6.2021.pdf

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saint approve vaccination

https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/church/news/church-makes-immunizations-an-official-initiative-provides-social-mobilization?lang=eng&query=vaccination

Jehovah’s Witness “Are Jehovah’s Witnesses Opposed to Vaccination? NO”

https://www.jw.org/en/jehovahs-witnesses/faq/jw-vaccines-immunization/

List compiled 9-30-2021

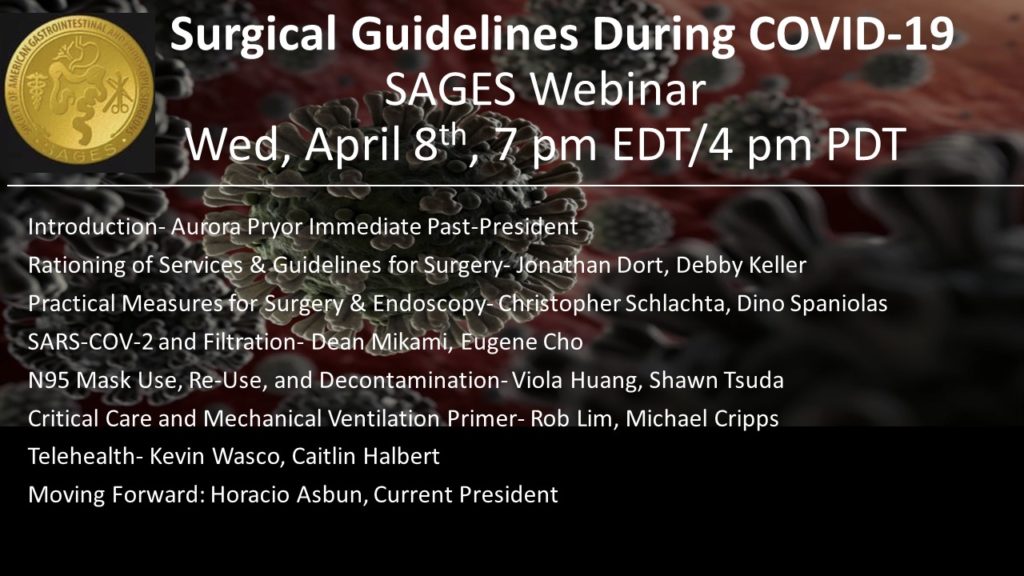

These are uncertain times for all of us facing the COVID-19 pandemic. As surgeons, we are seeing a halt to our elective practice, a transition to virtual clinic visits, and potential redeployment into areas of the front line in ICUs or medical wards that are outside of our regular practice patterns. Healthcare workers overall are facing potential equipment shortages, including in personal protective equipment. SAGES is working hard to provide resources to help you navigate this unfamiliar landscape. I can’t believe it was only two weeks ago that we postponed our annual meeting until August.

These are uncertain times for all of us facing the COVID-19 pandemic. As surgeons, we are seeing a halt to our elective practice, a transition to virtual clinic visits, and potential redeployment into areas of the front line in ICUs or medical wards that are outside of our regular practice patterns. Healthcare workers overall are facing potential equipment shortages, including in personal protective equipment. SAGES is working hard to provide resources to help you navigate this unfamiliar landscape. I can’t believe it was only two weeks ago that we postponed our annual meeting until August.